Watch the video above for the full story.

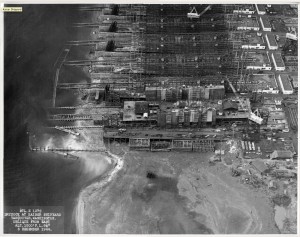

Historic Kaiser Shipyard, known to us today as the Columbia Business Center generates hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of jobs for Vancouver.

Historic Kaiser Shipyard, known to us today as the Columbia Business Center generates hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of jobs for Vancouver.

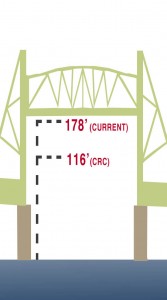

Why are these businesses in jeopardy? The proposed height of the replacement I-5 Bridge is too low for river traffic. Columbia River Crossing Light Rail Tolling Project, also know as the CRC is moving ahead full speed despite the impact the 116 foot bridge will cause on the local economy.

The current I-5 bridge’s vertical lift span is 178 feet, allowing the companies in the historic Kaiser shipyard to export a wide variety of products, many exceeding the newly proposed 116 foot limitation of the CRC.

History of Kaiser Shipyards

Henry Kaiser opened a yard in Vancouver and began producing baby aircraft escort carriers in January 1942. By the end of the war, 1,490 ships were built in his seven shipyards, an average of about one per day. Kaiser also built Liberty ships, oil tankers and landing ship, tanks (LST).

Today, this shipyard is known as the Columbia Business Center, one of the largest industrial parks in the Vancouver-Portland area.

Major Businesses Effected

Of the over 20 businesses housed in this industrial park, three major players are:

Employing over 700 workers. Greenberry Industrial has the ability to fabricate large tanks, pressure vessels, modules, bridge steel, and large structural components – that they ship them internationally and domestically.

A veteran-owned small business, Thompson Metal Fab, employs more than 250 people who build things like a 1.2 million pound Delta IV Rocket launch pad, oil rigs, and they also built towers for the Portland Aerial Tram that connects the city’s south waterfront with Oregon Health Science Center in the hills.

Founded in 1944, Oregon Iron Works, Inc. (OIW) is a pioneering force in the fabrication and manufacturing industries. Today, OIW builds a variety of products ranging from complex bridges to sophisticated military patrol craft in steel, stainless, aluminum, titanium or other exotic materials.

Conflict

The current I-5 bridge has a vertical clearance of 178 feet, currently providing unimpeded commercial river traffic. The CRC has proposed a new bridge with a height of 116 feet that will significantly impact at least three companies operating out of the Columbia Business Center: Greenberry Industrial, Oregon Iron Works and Thompson Metal Fab.

These three companies have over a thousand employees and bring hundreds of millions to the local economy.

The CRC feels they have sufficiently done their homework to develop a plan that will have the least impact in businesses that depend on the Columbia River to deliver products.

According to Nancy Boyd, Washington project director for Columbia River Crossing (CRC) project, the bridge design phase is now complete, and they are in the permitting/preconstruction phase – which includes finalizing funding. The final phase is construction itself.

“Other highway locations, or other drastically different designs,” said Boyd, “are not really being considered. We already have federal confirmation about how to move forward. This project is the culmination of regional planning and solving highest priority problems.”

“Other highway locations, or other drastically different designs,” said Boyd, “are not really being considered. We already have federal confirmation about how to move forward. This project is the culmination of regional planning and solving highest priority problems.”

The current design calls for a height of 116 feet, which Boyd said “impacts something less than seven vessels, one of which isn’t even built yet.” She also said the CRC staff is “still working on mitigation plan for impacted users, and is in close communication with three metal fabricators and marine contractors.”

However, the companies that will be impacted have weighed in:

In June 2012, CEO of Greenberry Jason Pond stated, “You might as well bankrupt us. I just don’t get it. This is a project that’s all about jobs. I just assumed that they wouldn’t kneecap these companies that are offering great jobs.”

“Greenberry Industrial is in favor of a new Columbia River bridge,” said Dan Rubin, Greenberry spokesman. “However, Greenberry currently delivers large fabricated projects under the existing Interstate Bridge with its 178-foot height, and some projects barely clear the span.”

Jason Pond, CEO of Greenberry Industrial, told law makers in Salem this week that while he supports the bill, the current height would negatively affect his business that has over 500 employees. He said 300 jobs could be lost. (The 116-foot proposal) is a huge impediment for us,” he said, “because the facility his company ships from is upriver from the bridge.”

TMF company president John Rudi is a strong supporter [of the CRC project] “right up until they put us out of business,” said Hunt. “They are not looking very far over the horizon.” Rubin put it this way, “If an undersized bridge is built, major companies that commission [massive fabricated structures] will simply take their manufacturing needs elsewhere, eliminating many jobs and the economic benefits for the region, permanently.”

Future Uncertain

Vancouver’s citizens oppose light rail, County commissioners oppose CRC.

The CRC’s goal, said Boyd, is to have all pre-construction documents in place within about a year, so that the project can get under contract by the end of 2014, providing the funding pieces fall into place.

With that goal in mind, the future is still unsure. Port Officials fear that without the $1 billion upgrade, shippers will avoid the port, because new supersized cargo carriers won’t be able to get under the bridge.

Many are asking: is this is the best design?

Many are asking: is this is the best design?

Besides the imminent impact on the business, Hunt said the 116-foot clearance was extremely short-sighted.

“We’re building a bridge for the next 100 years, and everything on the river is getting bigger. Everyone who uses it will tell you that,” said Hunt. “In 2006 we said we needed 125 feet – today we’d tell them we need 150 feet.”

Scott Patterson, C-TRAN’s director of development and public affairs, said that in light of C-Tran’s Proposition One bond failure last November, they are “in the mode of determining next steps.” He said a board workshop was scheduled for late February. Boyd said that light rail construction is covered by the federal grant, and the CRC is looking for $2 to $5 million per year for operational and maintenance funds.

Clark County Commissioner David Madore sums it up this way “Reducing the clearance for marine traffic from 177 to 116 feet would be a disaster for major Clark County businesses.”

Each day the cost of this project continues to rise, a firm date to start has not been established, there is fear that if Washington and Oregon do not act quickly the available money will go away. Since the residents of Clark County had clearly proclaimed (C-Tran Prop 1 ) they are not in favor of the current CRC plans, it only seems fair that community and government leaders may want to take a step backwards and begin listening to the taxpayers who are going to foot the bill.

The question still remains: Is this the best option for Clark County and Vancouver residents?

Only time will tell.

[...] of 178 feet. CRC proposed a bridge too low at just 95 feet with no lift for marine traffic, cutting off long time businesses that rely on adequate clearance to deliver products and services. The replacement bridge [...]