Finances play a big role in the running of a government agency. Each of the 39 counties in Washington has an elected treasurer who is responsible for tax and revenue collections, debt management, investing and banking services for the county’s money, record keeping and reporting, and finally budgeting.

Finances play a big role in the running of a government agency. Each of the 39 counties in Washington has an elected treasurer who is responsible for tax and revenue collections, debt management, investing and banking services for the county’s money, record keeping and reporting, and finally budgeting.

Glenn Olsen, Deputy Administrator for Clark County, is an expert in county budgeting. He developed the seminar “County budgeting, the perspective of budget writers.” It is designed to bring newly elected county officials up to speed regarding county finances and budgeting.

The following interview with David Madore and Glenn Olsen is presented in its entirety to provide residents of Clark County insights of the many technical facets related to Clark County’s budget.

The article below was submitted to COUV.COM by Glenn Olsen.

Why do They do That!

The Inner Workings of YOUR Government

Have you asked yourself, “Why do they do it that way?” Usually you are saying this to yourself about something the government has done that makes no sense to you.

We at couv.com cannot answer those questions for all the governments that exist in the U.S., but we can fill you in with a few answers about the one government that probably has more direct impact on your life than all the others: Clark County.

In a three-part series, couv.com is broadcasting an in-depth interview with county commissioner David Madore, to explain why the county operates as it does. In it he interviews staff about the inner workings that underlie the many varied services that are paid for by Clark County’s citizens.

In the first installment we lay the ground work for understanding how our county operates: what it is required to do by state and federal law and how that fits into our current economic situation. The first thing we learn is this is no typical enterprise. Counties are (constitutionally) an arm of state government. In practice, that means a county may do only that which it is specifically directed to do by state and federal law. This is the opposite of a private enterprise, which may do anything that is not prohibited by law.

That dramatically limits the choices a county has in fulfilling its mission to serve you. For example, finance in Clark County is not run by a single Chief Financial Officer (CFO). Instead, by state constitution the county has five elected officials who all have a voice in the financial operations of the county: the Treasurer, the Auditor, and the three County Commissioners.

The Treasurer collects taxes, manages cash and debt, and accounts for the funds related to those activities. Incidentally, the county Treasurer does not just collect property taxes for the county: he also collects taxes for the state, cities, schools, and the many other taxing districts inside the county.

The Auditor accounts for and controls the expenditure of funds.

The Board of County Commissioners controls the appropriation of (legal permission to spend) funds.

This complex arrangement was intended by the framers of Washington’s constitution to create checks and balances for you, the citizen, to make sure no one in the county can spend without oversight. It works admirably for this, but it creates systems and processes that do not seem sensible if you are used to a business model where one person can legally track and receive all revenue, account for that revenue as well as its expenditure, and can authorize where expenditures will or will not take place.

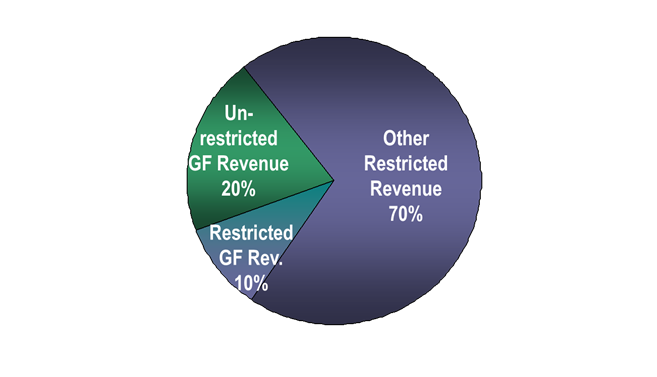

One of the first differences is that counties receive different “kinds” of money (revenue). Generally these fall into two broad categories: Restricted and unrestricted.

Restricted revenues are limited by law or by contract for specific uses, like roads. In order to make sure restricted funds are spent only where they ought to be, the county accounts for them in separate funds. Counties in Washington typically have one to two hundred separate funds. Each fund is a separate business, and it may have its own employees, buildings, and equipment. Money almost never can legally be moved between funds, so it is possible for one fund to be flush while another is broke. More to the point, there may be money for things citizens do not want and no money for things they do want. These rules are imposed on counties by the state or federal government.

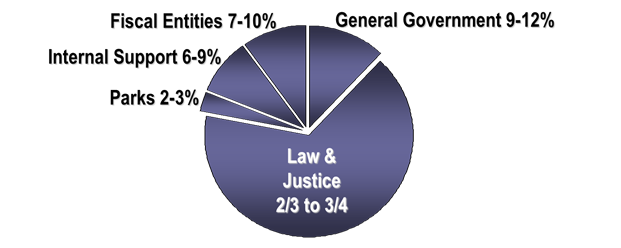

Restricted revenues are “off the table” when it comes to balancing the budget. Most of the activities that are supported by local tax dollars are in what is called the General (or Current Expense) Fund. The General Fund is about a third of total funds, and the only fund that is unrestricted. It pays for most of what people think of as county government, including law and justice, assessments, tax collections, elections, debt, building construction and maintenance, and parks.

Total County Revenue: Restricted and Unrestricted

Two-thirds to three-quarters of a county’s General Fund goes to the first item on this list of functions that it funds: law and justice (police, courts, prosecutor, juvenile, and jail).

General Fund Revenue: Expenditures by Function

Even in the General Fund a third of the funding is restricted, so that overall about 20 percent of revenue can be spent where your elected officials choose. The remainder may only be spent where the law requires. The largest areas which receive restricted funding are roads, human services, and public health. Should those areas run short of funding, the only option leaders have for reallocating money is from the General Fund, the one unrestricted source of funds.

Between the many functions the General Fund supports and it being the only source for supplementing other funds, there is enormous pressure on it. Furthermore, 70 percent of the General Fund goes to salaries and benefits. Against that backdrop, the two main revenue sources for the General Fund – property and sales taxes – have been hit particularly hard by the recession.

In Clark County that translated into a 20 percent reduction in forecasted revenue to the General Fund, after the recession started. This in turn drove a 15 percent reduction in personnel. Since that time General Fund revenue has been flat.

This means something different in a government than it does in a home budget, because virtually all the increases in expenses in Clark County are driven by population growth and inflation. Those two things did not stop, despite the recession. Since the economy is recovering, it may seem like this challenge is gone. In fact, it is just the beginning. The changes that affected the county rocked it to the core, and will affect how the county provides its services into the foreseeable future. How the county plans to rise to that challenge is the topic of the next part in this series.