Clark County is bucking a nationwide trend by being “the only urban county on the West Coast that is interested in growth,” according to international public policy consultant Wendell Cox. In his presentation at the Bridging the Gaps 2 event in Vancouver last October, Cox said the area has “so much potential that it is unbelievable and I personally think it is time that the people of Clark County begin to fashion their own future.”

Cox, who specializes in transport and demographics, spoke on how mobility and land use drives economic growth in urban areas, relating this to Portland, Clark County, and the Columbia River Crossing light rail project.

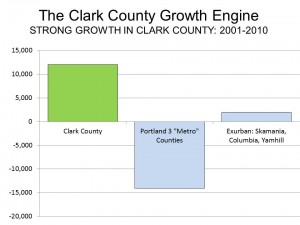

As for Clark County’s economic growth potential, a job creation graph from 2001 to 2010 shows that Clark County gained over 10,000 jobs while Portland’s three metro counties lost nearly 15,000.

The more mobile we are, the greater the economic growth

Cox, a one-time advocate of light rail said that many people “like to tell you that the automobile is terrible, that it gets in the way of economic growth. Well the fact is, all the evidence suggests that the more mobility we have, the better we do in economic growth.”

Cox says the two economic imperatives to ensure economic growth and job creation are:

* Minimize travel time, making it possible for people to get anywhere quickly;

* Minimize cost, do it as inexpensively as possible.

Empirical data backs this up. The more trips that are taken by motorized transport the higher the gross domestic product (GDP) per capital growth in that country. The United States is at the top.

Another survey measuring the median travel time to work shows that transit takes 47.1 minutes while commuting by car takes 21.4 minutes, leading Cox to say, “If you try to get people out of cars and into transit you are in favor of poverty because you are in favor of strategies that reduce economic growth.”

Dubious economic success for Portland’s anti-auto, pro-densification policy

Cox says that “one of the ‘great’ things planners are attempting to do is to increase densities.” So what are the consequences of greater densities in major metropolitan counties?

Data correlating population density per square mile and daily vehicle travel per square mile show that when density goes up traffic densities go up as well. Likewise, data correlating population density and air pollution shows that as population density increases so does air pollution tons per square mile.

“You know, you are told by planners that if only we densify, if only we make our cities more dense and get out of cars, we are going to have better air quality. Not a chance,” says Cox.

Denser urban areas with greater population per square mile slows traffic, increases fuel consumption, and leads to a more polluted environment. “The fact is the worst air pollution is where the density is the highest because that’s where the cars are polluting,” Cox says.

Cox had harsh criticism in particular for Portland planners, saying they are, “the worst in the world, they really are, and I’ve been around the world on this issue,” adding that Portland has the most radical densification, anti-suburban, and anti-automobile policies in the United States.

Cox points out the irony in a datapointed.net map showing the “decentralization” growth pattern in Portland from 2000 to 2010, saying, “You would think that the growth would probably be toward the center,” yet the map clearly shows that the greatest growth in the Portland metropolitan area was actually at the edges of the city.

According to Cox, a big problem with planners is that they think only the downtown counts. The fact is, in 2010, only nine percent of the employment in the Portland metropolitan area was downtown. “That 91 percent cannot be served by transit. Pure and simple, it isn’t anywhere in the world and it isn’t in Portland,” Cox says.

The transit experience is also exacerbated by the “last mile problem” that plagues all transit systems. To ride light rail Cox says, “You have to get to the train and then you have to get from the train to get to where you are going.” A 2008 Brookings Institute study found that there isn’t a major metro area where you can get to more than 10 percent of jobs in 45 minutes by transit. Portland reaches nine percent.

This has not deterred TriMet spending an additional $5 billion in the last 25 years to build and run transit in the Portland metropolitan area. What has the money purchased? TriMet’s transit market share has dropped from 10 percent to 6.2 percent. Meanwhile, recent studies show that telecommuting is now significantly larger than transit’s market share.

CRC driven by flawed and expensive ideas

Planners continue to find funds and subsidies to promote their vision, something Cox learned early on when he served on the L.A. County Transportation Commission. “The public sector has no perception of money; they seem to think that money will always be there and there will always be more,” he says. “We need people running our public agencies that recognize that every dollar needs to be used to the best effect.”

This criticism rings loudly in Cox’s review of the Columbia River Crossing Light Rail project (CRC), where he ticks off a number of issues, such as the erroneous notion that the feds will not finance the bridge without tolls and the “absolute crazy and unnecessary” waste of money upgrading parts of the freeway without increasing capacity. He also says a fair review process would have studied a bridge-only alternative rather than only “the politically correct” light rail system.

And how effective will light rail be in improving economic growth? What is now a 15-minute bus ride from Vancouver to Portland will become a 30-minute ride with light rail.

Cox was humored and amazed about a 2005 study – written about earlier on COUV.COM – that is still sitting on the Oregon Department of Transportation website that says that with ongoing preservation the two Interstate Bridges can serve the public for another 60 years – and transportation experts estimate a replacement bridge could cost $500 million to $1 billion.

It was clearly apparent to Cox that the “flawed, incomplete, and expensive” CRC process fails the economic imperatives for economic growth and job creation because it fails to minimize travel times and it costs more than necessary.

Cox says the planning process is so flawed, “it needs to be started again.” The CRC needs to “go back to the drawing board with an honest process and minimum cost that solves the problem.”

Clark County is “the economic engine of the Portland area,” he said. “It is time for Clark County to wake up and recognize the value it has and what it can accomplish.”

*********

Watch full version of Wendell Cox’s Bridging the Gaps 2 presentation here.

Related COUV.COM Article: John Charles: Transit oriented development coming to Clark County?